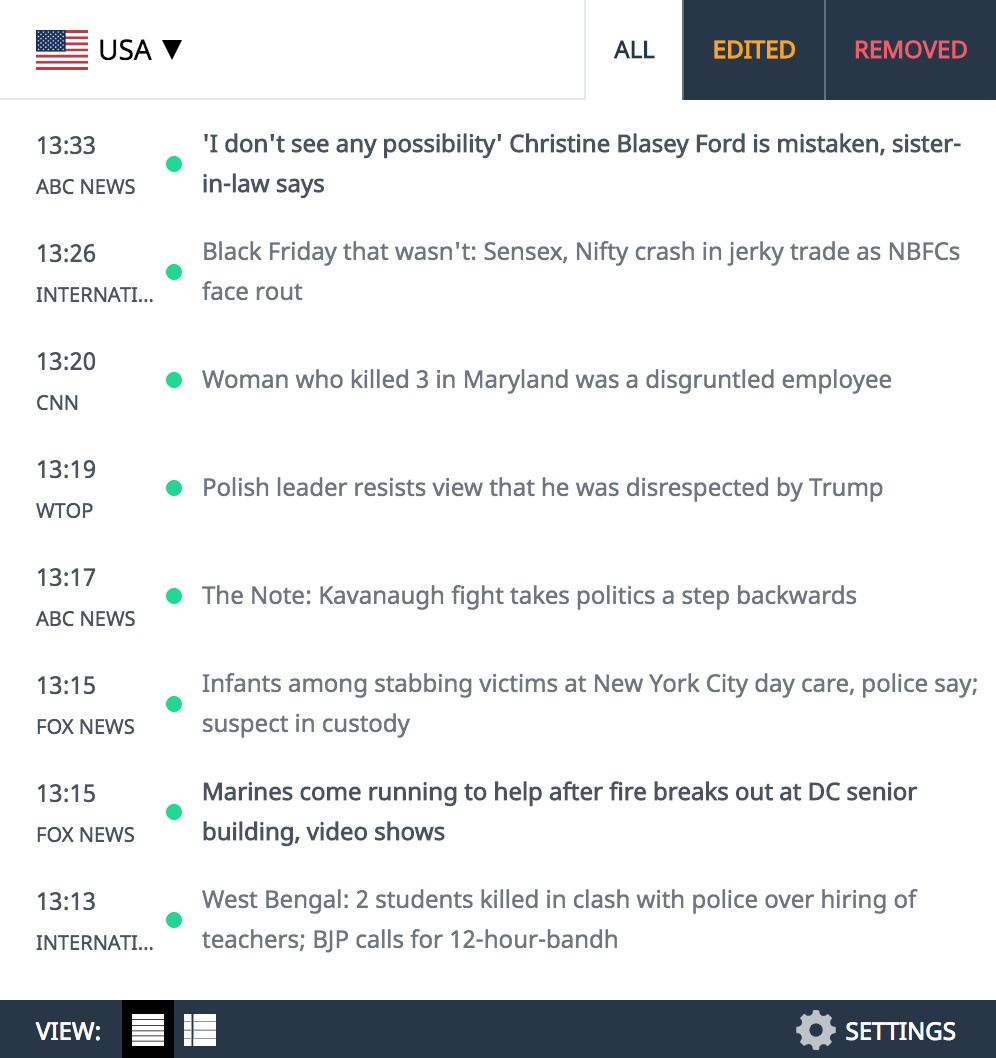

Shlomo Marmor, the owner of a flower store on Yehuda Halevi Street in Tel Aviv, feels deceived.

His shop, which his family has run for over 70 years in the same location, is right across from a shiny new light-rail station that exits onto a promenade in the middle of the two-way street.

The area has been a construction site for nearly a decade as a string of delays and controversies pushed back the opening of the Tel Aviv light rail. The inaugural Red Line finally opened last month and runs 24 kilometers from Petah Tikva to Bat Yam via Tel Aviv’s economic centers.

On this summer morning in mid-September, just before the Rosh Hashanah holiday, Marmor was at his shop preparing floral arrangements for customers ahead of the Jewish New Year celebrations, and observing as every now and then a few passengers — less than a handful — emerged from the underground station and spilled onto the road.

“Nobody comes out of the station. We hoped the start of the train line would bring us some relief, but things are even worse now,” Marmor, 70, tells The Times of Israel.

Sign up for ToI's free Real Estate Israel newsletter

Before the start of the rail works, he employed two salaried workers. Now, because business is so bad, he works most days alone, and he has never received any compensation for the road closures.

“They told us it would be ‘hard today but good tomorrow.’ But we are still looking for the good. It’s not good,” Marmor says.

Illustrative: A test drive of the light rail in Tel Aviv on August 16, 2023. (Avshalom Sassoni/Flash90)

Businesses and residents situated along the route of the first phase of the Light Rail Transit (LRT) network hoped that finally, with the start of the first rail services on August 18, they would witness a bonanza of work and activity, compensating them for eight painful years of road closures, blocked access and building-site dust and noise.

Those hopes, however, seem to be fading for now, as many store owners say that whatever renaissance the train may bring to their street in months or years may be too little, too late for some.

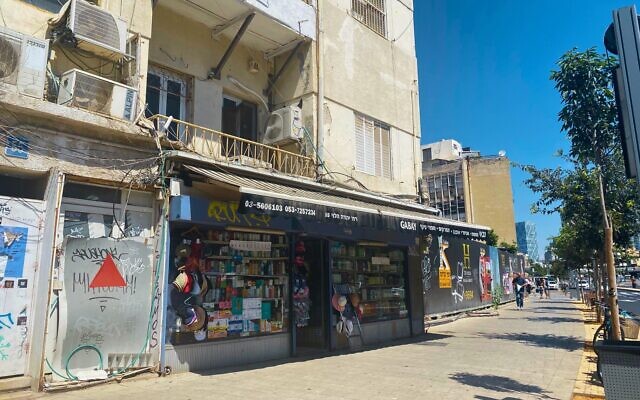

Ronen, the 54-year-old owner of a cosmetics and house-cleaning items store called Gabay, also on Yehuda Halevi Street, was sorting through packages on the floor of his empty store, a day before the eve of the Jewish New Year. He’s run the shop on rented premises for the past 30 years.

“Look at how many people are coming out of the station,” Ronen says, standing at the entrance to the shop, squinting in the bright Tel Aviv sunlight. “Nobody. This road used to be full of people. And today is a day before the weekend and the Jewish New Year. It should be busy. But it’s not.”

“They told us that, with the train, things would be great. But it is all a bubble. It will take years until it all comes back.”

‘A street that has been destroyed’

The Dankal Red Line, the first stage of a plan for a larger Light Rail Transit (LRT) network, is meant to be the backbone of the Tel Aviv metropolitan area’s mass transit system.

It passes through some of the most crowded areas of the metropolitan area, serving as many as 234,000 passengers a day, according to the website of NTA Metropolitan Mass Transit System, known in Hebrew as Neta, which is building the system.

So far, business daily The Marker reported this week, traffic has been less than half that expected, at some 110,000 passengers a day.

The Red Line starts at the Petah Tikvah central station and continues to Beilinson Hospital and along Jabotinsky Road in Bnei Brak and Ramat Gan. It then passes near the Savidor station in Tel Aviv and the Azrieli Center, and continues along Begin Road to south of the Kirya military base, Neve Tzedek, Jerusalem Boulevard in Jaffa, and ends in the south part of Bat Yam.

One of the three exits of the Allenby station in Tel Aviv is on Yehuda Halevi Street.

The Gabay store on Yehuda Halevi Street, in Tel Aviv, September 2023. (Shoshanna Solomon / The Times of Israel)

Ronen says he remembers very clearly the day work for the train started on Yehuda Halevi on August 1, 2015. “The street got a shock. There was a two-meter wall in front of the stores along Yehuda Halevi Street from Ramchal to Allenby,” he says, along some 800 meters of road.

Access to the stores was completely cut off and closed to traffic, he adds, with just a tiny pathway for pedestrians to walk on, which was “just a few tiles wide.”

This hurt the businesses, forcing many to close, he says, including coffee shops, food stands, and restaurants that peppered a street that had been generally used to a bustle of people, cars, and buses. Businesses, including bank branches, hairdressers, and large insurance firms, with hundreds of employees, relocated elsewhere because of the mess.

“People used to walk around on the street. . . but when they started the work on the light rail people moved their offices and activities to other areas in the city,” says Ronen.

Since then, Ronen has been struggling to keep his business alive, amid the dust and the noise and the plunge in customer numbers and turnover, he says. “It is very difficult to bring back life to a street that has been destroyed.”

New stores that recently opened on the street in the hope of renewed traffic brought on by the train have shut down, he notes. “A sandwich shop opened and closed again within six months, and a new second-hand clothes store suffered a similar fate. They saw it was not worth opening. There is no work and not enough customers.”

Before the rail work started, four families used to work together in Ronen’s store and live off its profits. Now, there is barely enough for one family, he says.

“It’s just me and my children running the shop.”

Ronen at his cosmetics and house-cleaning items store on Yehuda Halevi Street, Tel Aviv, September 2023. (Shoshanna Solomon / The Times of Israel)

Ronen said he survived by cutting back on stock, starting delivery services, and working even harder. Profitability and revenues plunged anyway. “I said to myself, I am now running a completely new store. I felt I was starting over. I fought to keep this place open,” he says.

He said he didn’t get any help from the government for the huge disruption caused by the street closure – “not in municipal taxes or anything.”

As he speaks, clients start walking in. One woman is looking for hair dye, and Ronen spends a few minutes discussing with her which tone would suit her best. A silver-haired woman comes in looking for a good hair balm. Ronen explains the alternatives, while also combing her hair with one of his new brushes (which she promptly buys) and gently applying the balm he recommends (which she also purchases). Another woman walks in looking for nail polish, to which he adds a few complementary cotton balls.

“I’m here for whatever you need,” Ronen tells his customers. Some seven people came into the shop in the 15 minutes this reporter was there, and Ronen’s cell phone kept on ringing.

“If you think this is busy, you should have seen what it used to be before the start of the work,” he says. “This is busy for one person, not a group of four families. What you saw here is not work.”

In anticipation of a bonanza that hasn’t come, the landlord raised Ronen’s rent twice, he says, and he is now paying 15% more than before.

Roee Cohen, the president of the Israel Federation of Small Business Organizations (Lahav), tells The Times of Israel in a phone interview that “there were expectations that the start of the train service would lead to a renaissance of the area. These expectations have been dashed for now.”

“Not even one shekel was given as compensation to businesses along the line,” Cohen says. “That was the big failure: the complete lack of understanding and lack of empathy for the businesses that are on the route of the train.”

To help the businesses, NTA Metropolitan Mass Transit System and the Tel Aviv municipality said they would set up a NIS 10 million joint fund, launched in 2018, Cohen explains.

Construction workers at the intersection of Allenby and Yehuda Halevi streets in Tel Aviv, on August 4, 2015, where construction began on the new light rail. (Miriam Alster/ FLASH90)

But once the fund was set up, “we saw it was all a bluff,” says Cohen, as the criteria to get help didn’t take into consideration the decline in turnover, nor did it exempt the businesses from the municipal tax (arnona).

The fund helped only marginally, he added, paying for 50% of the costs of taking the businesses’ activities online, for example, or paying part of the costs of improving store access amid the huge construction mayhem.

“They prescribed paracetamol for a migraine,” Cohen says.

Hardship and survival

Not all stores on Yehuda Halevi are suffering as much: Anjaly has been selling stylish yoga and workout clothing for men and women for 15 years at the same address, and Hagit, a saleswoman, said the store’s loyal customers continued to shop amid the building site upheaval. Even so, she says, there was a drop in sales during the construction period.

“There was a barrier in front of our show window.”

Even now, she says, not many people come out of the train station. “It’s not very busy. It will take time. But I’m not worried, because it’s already significantly better than what it was during construction.”

Hagit, a saleswoman, at the Anjaly workout wear store on Yehuda Halevi Street in Tel Aviv, September 2023. (Shoshanna Solomon / The Times of Israel)

Hagit adds that she has directly benefited from the light rail, as it takes her just an hour now, door to door, to get to work by train, getting on at Hadera Station and getting off at Allenby Station, exiting onto Yehuda Halevi. “The train has made it easier for me to come to work,” she says.

Similarly, Ronny, the owner of Azura, says loyal customers continue to frequent his restaurant, which serves up piles of steaming Kubbeh – semolina dumplings filled with meat and cooked in a soup — and additional Mediterranean delicacies to hungry patrons.

“It was hard during the work and dug-up streets, but we managed to survive,” Ronny says, even if customers had to make a wide detour, walking all the way to Allenby and back, to access the restaurant. “There was a decline in business,” he says. But now, activity is back to pre-2015 levels, and no workers have been laid off by the family-run business.

With the start of the work on the additional rail line, the Purple Line, going from Tel Aviv through Ramat Gan to Yehud-Monosson, a city in central Israel, some additional 1,000 businesses along Tel Aviv’s Allenby Street, which has already been cut off from traffic since August 5, will be struggling for survival, said Lahav’s Cohen.

“We hope lessons will have been learned from the experiences of the Red Line,” he says.

Ronny, the owner of the Azura restaurant on Yehuda Halevi Street in Tel Aviv, September 2023. (Shoshanna Solomon / The Times of Israel)

On August 28, Lahav petitioned the High Court of Justice to ensure that businesses along the Purple Line would be compensated based on the drop in revenue compared to the turnover of the previous year.

The closure of Allenby to car traffic for the sake of the light rail works will deprive some 1,000 business owners of their livelihood, as all the activity of shoppers on the street will almost entirely stop for the four-and-a-half years of the duration of the work, the petition said.

Without compensation, these road closures will be a “fatal blow” to the businesses that have characterized Allenby for many years, the petition said.

“Businesses, from one minute to the next, without any consultations and no one to talk to…have seen their turnover drop by 50%-60% while costs and debt remain the same,” says Cohen. “They now have to make people redundant and cut costs and activities.”

Too late?

Back at Marmor’s flower shop, the 70-year-old owner was busy making colorful arrangements for customers.

“Because tomorrow is the New Year and people buy flowers, I have an assistant helping me today. But for eight years, I have been working alone. For eight years, we lived on a construction site.”

Ahead of the start of the train work, Marmor considered refurbishing the store, anticipating a business boom that never materialized, he says. “Luckily, we didn’t invest any additional money in here.”

Even if things pick up in a few years, it will be too late for him, he says.

“I am already a pensioner. In another five years, I will be 75. People are now used to going elsewhere, and they don’t come here anymore. Today is the eve of a holiday, and there’s no one,” he laments.

NTA was not immediately available for comment.

A spokesman for the Tel Aviv municipality sent The Times of Israel the following response:

“The light rail is a national project under government responsibility, located in five different cities. The Municipality of Tel Aviv-Yafo is the only one that has taken it upon itself to help in a special way through the establishment of an aid fund, in cooperation with the ministries of finance and transportation, intended for businesses facing excavation works of underground stations.”

“Contrary to what has been claimed, the fund was able to help businesses along the train route. On the Red Line, assistance was given to 21 businesses in the amount of approximately NIS 3.7 million: 11 businesses at Allenby Station in the amount of NIS 2,325,000; one business at Yehudit Station in the amount of NIS 10,500; nine businesses at Carlebach Station in the amount of NIS 1,437,000,” the statement read.

“Over the years, the municipality has applied several times to the Finance Ministry with a request to expand the coverage of the fund also to businesses that are not adjacent to underground works, but no agreements have been reached. As for the property tax discount, this is not under the authority of the municipality but under the authority of the ministries of interior and finance. However, the municipality is doing everything in its power to help in other ways, such as granting an exemption from paying the fee for tables, chairs, and awnings and the night permit fee for businesses located on the light rail route,” the municipality said.