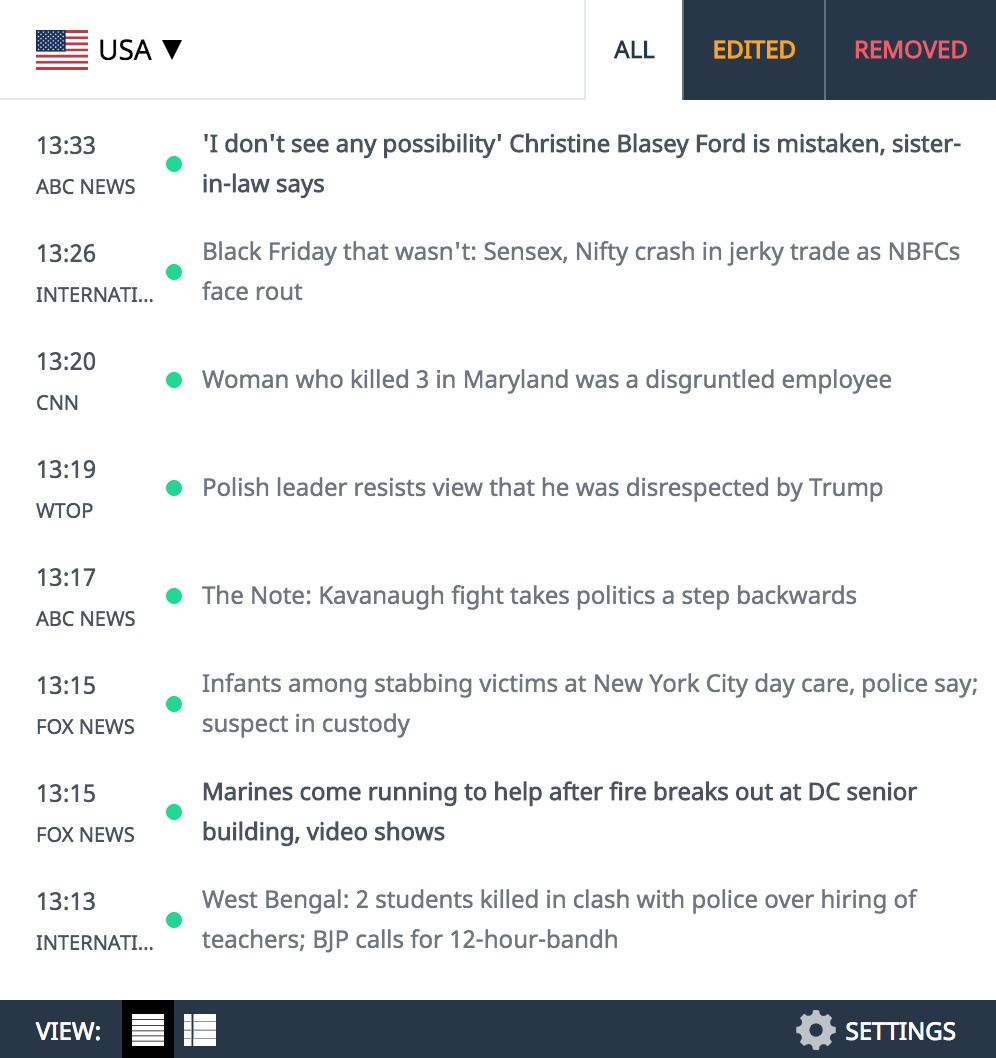

FAIRFIELD, Connecticut — Artist Arthur Szyk’s January 1942 cover for Collier’s International pulled no punches.

Hitler stands behind a globe while a pair of skeletons wearing SS uniforms scurry across. Meanwhile, Herman Goring, Heinrich Himmler and Joseph Goebbels pin Nazi flags across Europe as a snake tattooed with swastikas slithers past the bodies of Phillippe Pétain and Benito Mussolini.

“Szyk is saying, ‘Wake up!’ He’s trying to shake Americans into acting against the world domination the Nazis were bent on. The malevolence just comes through in this work,” said Carey Mack Weber, executive director of the Fairfield University Art Museum.

Indeed by the time the cover art — titled “Madness” — ran that winter, the Nazis had already murdered hundreds of thousands of Jews and the Third Reich occupied the majority of Europe and parts of North Africa.

It was one of eight covers the Polish-Jewish émigré did for Collier’s. It’s also one of 50 original works now on exhibit through December 16 in “In Real Times. Arthur Szyk: Artist and Soldier for Human Rights,” at Fairfield University’s Bellarmine Hall galleries.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

The show, originally from the University of California’s Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, is the largest exhibition of Szyk’s work in the northeast in over 50 years. It highlights the lifelong mission of the artist — who spent his final years in the nearby town of New Canaan — to elevate democratic ideals and fight injustice.

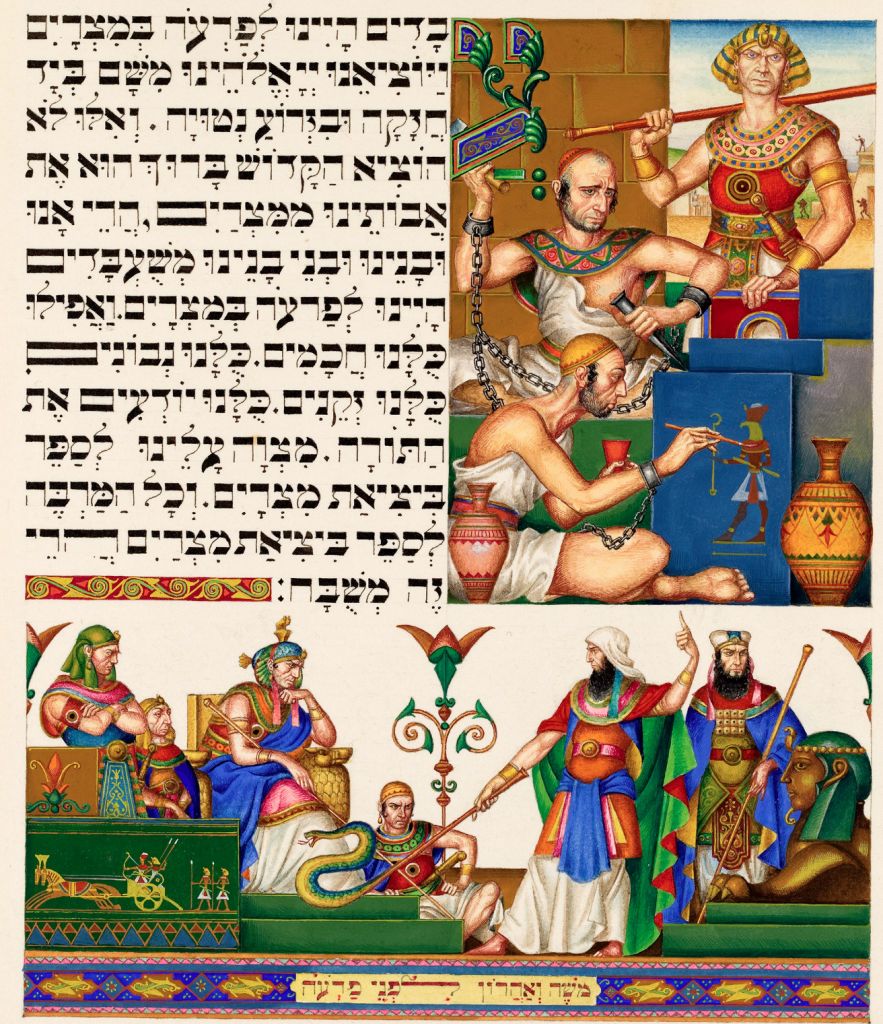

Artist Arthur Szyk working at his desk in New York City, 1944. (Courtesy: Irvin Ungar, curator emeritus, The Arthur Szyk Society)

“It’s especially timely given the fight for human rights, questions about migrants and refugees, rising antisemitism and the way freedom of expression is being thwarted,” Weber said.

Born into a middle-class family in Łódź in 1894, Szyk lived a life framed by two world wars, the rise of totalitarianism in Europe, the birth of the State of Israel, McCarthyism and American racism and antisemitism.

Szyk fled with his wife and two children to London soon after Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. The family immigrated to the United States in 1940.

“It was big news that he had arrived. He was a big deal,” said Philip Eliasoph, an art history professor at Fairfield University and curator of the exhibit.

Arthur Szyk, ‘Madness,’ 1941, watercolor, gouache, ink, and graphite on paper. (Courtesy of Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection, The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, University of California, Berkeley)

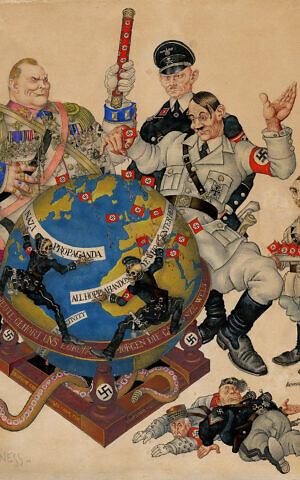

Szyk’s work had previously been exhibited in the Brooklyn Museum and graced the covers of Manhattan and Brooklyn phone books. Additionally, many Americans were familiar with the Szyk Haggadah, which the artist had illustrated in Poland between 1934 and 1936. When it was finally officially published in the UK in 1940, The Times of London proclaimed the Haggadah “worthy to be placed among the most beautiful of books that the hand of man has ever produced.”

The richly illustrated Haggadah was also one of, if not the most, expensive new books in the world at the time, Eliasoph said. Original copies sold for $500. By way of comparison, a 1940 Ford standard model sold for $600.

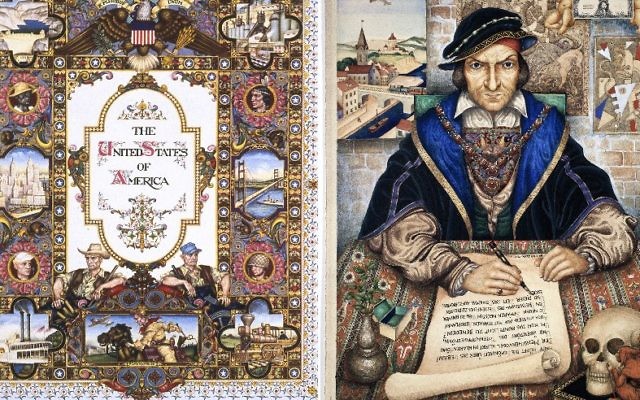

The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” column from August 2, 1941, declared that “the leading miniature painter” was turning from his work celebrating American subjects, such as the Declaration of Independence, to Hitler, Goebbels and the plight of Jews “as a matter of duty.”

Each of the exhibit’s six sections highlights a facet of human rights.

In “Human Rights and their Collapse” visitors see the way European democracies fell like dominoes. There hangs Szyk’s March 1943 “Ballad of the Doomed Jews of Europe.” The illustration, which also appeared as an advertisement in The New York Times, shows an emergency telephone call made from Europe going unanswered. The black and white illustration surrounds a poem by Hollywood screenwriter Ben Hecht.

An x-ray of ‘We Were Slaves to Pharaoh’ revealed a swastika on Pharaoah’s breastplate that was painted over. (Courtesy of The Arthur Szyk Society)

Szyk’s concern for refugees like himself is clear in “Rights of the Global Refugees.” His 1943 drawing of two Jewish children under the caption “To be shot, as dangerous enemies of the Third Reich!” hangs near “De Profundis. Cain, Where is Abel Thy Brother?” The latter illustration, first published in the Chicago Sun in 1943, depicts a pile of bodies of Jewish Holocaust victims.

“The Right to Resist” displays works honoring Jewish fighters. For example, Szyk’s 1939 “Defenders of Warsaw” shows strong, albeit weary, men.

“They are heraldic figures, almost larger than life. He shows them as having incredible strength in their legs and their arms,” Weber said.

In “The Right to America,” several paintings and illustrations call out American antisemitism and racism. One such work is a 1949 illustration, “Do not forgive them, O Lord, for they do know what they do.”

The image, which ran in the left-leaning Daily Compass, shows an African American solider kneeling with a noose around his neck. He’s wearing a Purple Heart medal and a crucifix on a chain. Behind him stand two hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan, their guns held high.

Below the image Szyk wrote: “Each Negro lynching is a national disaster, is a stab in the back to our government in its desperate struggle for democracy.”

To Eliasoph this illustration, as well as others that target American antisemitism and racism, are a testament to Szyk’s love for his adopted country.

“He’s saying here are our flaws, but we are a great democracy and we must do better,” he said.

And yet that same year the House Un-American Committee opened an investigation into Szyk. The news shattered Szyk, who once wrote of the United States, “At last I have found the home I have always searched for. Here I can speak of what my soul feels.”

‘The United States of America’ (1945), left, and ‘The Scribe’ (1927), by Arthur Szyk. (The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, University of California, Berkeley)

Szyk suffered several heart attacks before dying at his home in New Canaan in September 1951.

“I believe the stress of the investigation killed him,” Eliasoph said, adding that the charges were proven unfounded.

Beyond the way Szyk confronted tyranny and how his work speaks to America’s current political crisis, one of Szyk’s greatest legacies is that he never tried to hide who he was, Eliasoph said.

“He does not hide his identity. He was a magnificent Jewish artist and ambassador of the Jewish people,” Eliasoph said.