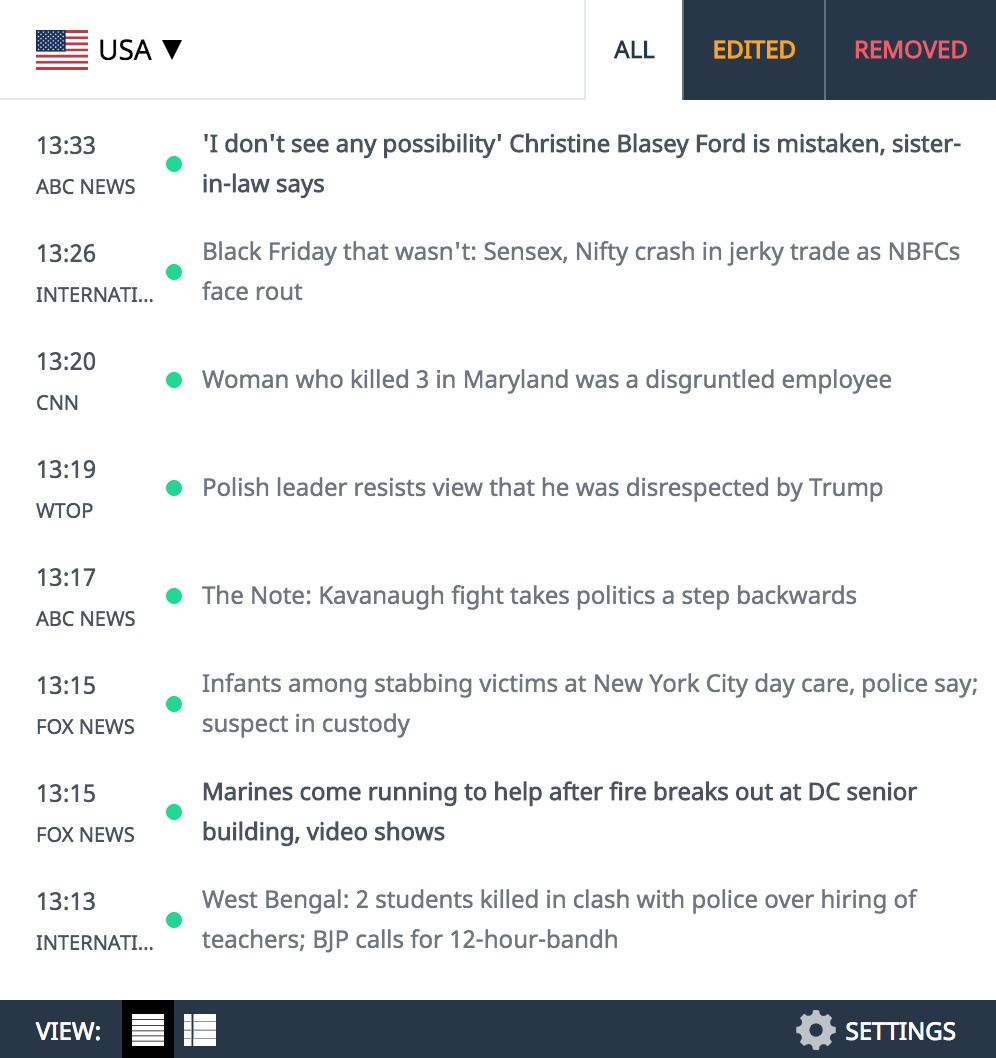

Canadian singer Carly Rae Jepsen performs onstage during the All Things Go music festival at Merriweather Post Pavilion in Columbia, Maryland. — AFP pic

COLUMBIA, Oct 1 — Back in 2006, Spotify was a nascent start-up, your average stateside concert tickets went for US$40 (RM188) and many fans learned about the best new music from blogs like All Things Go.

Nearly twenty years later, most people find new artists via algorithms and the average US concert ticket costs US$250 — double what it was just five years ago.

All Things Go, however, has grown into a thriving indie music festival in a world where live events are increasingly owned by a handful of companies.

Now in its ninth year, the festival — whose name derives from a Sufjan Stevens lyric — embodies the same ethos as that of music blogging’s turn-of-the-millennium heyday.

It focuses on emerging artists while prioritising the experience of live performance over creating viral moments or appealing to social media influencers, both now dominant forces at more corporatised festivals.

The event kicked off its 2023 edition on Saturday at Maryland’s historic Merriweather Post Pavilion amphitheatre, spanning two days for the first time, with a women-led bill and headliners including Lana Del Rey, boygenius, Carly Rae Jepsen and Maggie Rogers.

The festival’s founders first began transitioning from their corner of the internet to live venues by holding monthly club nights in Washington DC, hosting artists who were popular on their blog.

They held their inaugural festival at Washington’s Union Market in 2014, later expanding to the Capitol Waterfront in 2016 before moving in 2021 to Merriweather, which can host up to 20,000 people per day.

“I think for us it really is about the music,” co-founder Stephen Vallimarescu told AFP. “It’s about creating the experience where you want to see the artist at noon as much as you want to see the headliner at 10.00pm.”

And with two stages “we basically set it up so that you can see every single band on the bill.”

That’s a far cry from the experience fans get at festivals like Coachella, where hundreds of thousands of people gather annually in the California desert for two three-day weekends featuring dozens of artists and six stages, with overlapping set times.

At that event, music is not the only draw: there are giant Instagrammable sculptures, a Ferris wheel, special food and drink attractions, celebrity and influencer-filled VIP tents and after-parties.

All Things Go’s organisers are going for a more boutique vibe, said Vallimarescu.

“It is pretty unique to look at our community — like these are music fans who go to 10, 20, 30 shows a year, and they come to the festival early,” he said.

“They’re there for the music, they’re not there for Ferris wheels, or Instagram posts.”

The All Things Go music festival kicked off its 2023 edition yesterday at Maryland’s historic Merriweather Post Pavilion amphitheatre, spanning two days for the first time, with a women-led bill and headliners including Lana Del Rey, boygenius, Carly Rae Jepsen and Maggie Rogers. — AFP pic

Consolidating festival market

It’s no small feat to host an independent music festival these days. All Things Go certainly isn’t the only event of its kind, but the landscape is increasingly dominated by giant live performance promoters like AEG and Live Nation, the two largest in the world.

In 2018, a group of indie festivals in Britain decried Live Nation’s dominance of the industry there, accusing the California-based behemoth of practices including exclusivity deals with venues that “stifle competition.”

In 2022, Live Nation — which in addition to controlling significant swaths of the touring industry also owns Ticketmaster, the American ticketing titan — recorded US$16.7 billion in revenue, promoting 43,644 events including concerts and festivals worldwide, according to data compiled by Statista.

Most major music festivals are under the umbrella of Live Nation — Bonnaroo, Lollapalooza and Isle of Wight among them — or AEG, which owns the company behind Coachella.

Vallimarescu noted that many indie festivals folded as the performance industry took a major hit, especially post-pandemic.

“The reality is that the larger festival ecosystem is very much being consolidated,” said fellow co-founder Will Suter.

“Globally it’s the reason you see kind of the same headliners across most of festival lineups these days.”

All Things Go has lasered in on indie rock, a strategy Suter said works to help it stay competitive in the corporate-dominated festival scene.

“Doubling down on our genre, and really offering value to the consumer that justifies the ticket price” is a goal, he said, with the hope that fans are interested in 12 to 16 artists on the lineup, can actually manage to see them all, and are enticed to come back.

Tickets to All Things Go this year ranged from US$105 to US$500, the pricier end being heavy on perks.

The festival has also stood out by booking mostly women and non-binary artists — from the headliners down the bill — in an industry that’s still heavily biased towards men.

Suter praised fellow indie festivals across the United States “that are working day in and day out” to keep live music accessible and eclectic.

“It’s a community, including with shoulders to cry on,” he said.

“It’s cool to see different independent festivals still working.” — AFP